by Chelsea Stewart-Fusek

Cascadia Wildlands Legal Intern, Summer 2020

Beaver moving mud to its dam or lodge (photo courtesy of Cheryl Reynolds, Worth a Dam, MartinezBeavers.org).

The North American beaver (Castor canadensis) is a primarily nocturnal, semi-aquatic rodent that is known as an ecosystem engineer because its dam-building behavior drastically changes the habitat in which it lives. Beavers are also considered a keystone species because their removal has far-reaching impacts on other wildlife species and on the ecosystem as a whole. Beavers play a fundamental role in creating and maintaining a diversity of flora and fauna associated with the Pacific Northwest’s streams, rivers, and wetlands, and protecting them is key to restoring and maintaining healthy waterways in Oregon.

Prior to European arrival in North America, Oregon’s streams and rivers may have harbored an estimated one million North American beavers. Unfortunately, historic beaver eradication efforts to create a “fur desert” in Oregon—with the purpose of preventing fur trappers from coming to the region—resulted in dramatic declines of the species. While beavers have rebounded in many areas, trapping continues to this day.

Dam! We Need Beavers.

Adult beaver and two kits along their dam (photo courtesy of Cheryl Reynolds, Worth a Dam, MartinezBeavers.org).

Beavers build dams to create a safe pond where they can build their “lodge.” A beaver lodge is built out of twigs, sticks, rocks, and mud, and has an underwater entrance. Inside their lodge, beavers have a protected place to sleep, raise their offspring, stay warm, and avoid predators. Beaver dams and the ponds they create also provide a number of critical ecosystem services.

Beaver dams alter the geomorphology of riparian habitat, causing stream ecosystems to develop complexity. Beaver ponds increase the surface area of water several hundred times, which promotes vegetation growth by increasing the amount of groundwater for use by riparian plants and wetland areas. This positively influences the diversity and survival of many other wildlife species and insects. Deep root systems from these plants maintain bank structure and combat erosion, while the trees and plants themselves provide shade needed to keep water cool and fish populations thriving. Beaver ponds store carbon in the form of settled organic matter. One 2013 study found that beaver complexes on a system of 27 streams within Rocky Mountain National Park at one point stored more than 2.6 million megagrams of carbon—an amount equivalent to the carbon stored by 37,000 acres of typical forest. These ponds also create critical refugia and fire breaks during wildfire events.

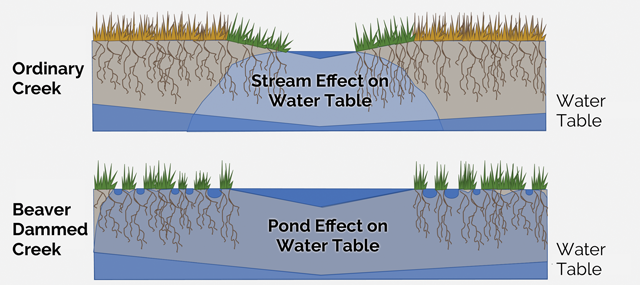

Diagram of effect on water table levels for a “no beaver stream” vs. “beaver dam stream” (graphic by EarthMagazine.org of the American Geosciences Institute).

Studies conducted in streams along the Oregon coast have shown that beaver dams enhance over-wintering habitat for Coho salmon by creating ponds that can shelter young salmon from swift, high water flow events. The readily available food and protective environment in beaver ponds also lead to increased salmon growth and survival. Michael Pollack of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has studied the relationship between beavers and juvenile salmon for over a decade (Pollack et al. 2004). His research identifies the important relationship between beavers and juvenile Coho survival and calls for watershed restoration activities that emphasize returning beavers to areas in which they no longer exist.

Free Restoration Services Stunted by Sportsmen-Friendly Bureaucracy

Across Oregon, federal agencies, state land managers, private industries, conservation organizations, watershed counsels and others have spent enormous amounts of time and resources to improve watershed conditions and aid in aquatic species recovery. These are outcomes provided by beavers at no cost. The state resources used to achieve these ongoing efforts are greatly enhanced by the presence of active beaver colonies and are therefore significantly hindered by the hunting and trapping of beavers.

Beaver kit(juvenile), chewing on vegetation in its pond (photo courtesy of Cheryl Reynolds, Worth a Dam, MartinezBeavers.org).

Cascadia Wildlands and dozens of other organizations have requested Oregon’s Fish and Wildlife Commission end the hunting and trapping of beavers on federal lands and instead create practices that align with our state’s already established aquatic restoration efforts. The Oregon Fish and Wildlife Department (ODFW) has itself stressed the importance of beaver dams to Oregon’s ecosystems within its Conservation Plans, yet it refuses to support the banning of beaver trapping on federal lands. To preserve the status quo, the ODFW relies on faulty science and asserts without evidence that banning trapping in these areas would do nothing to improve beaver numbers or assist in restoration efforts.

On June 12, 2020, the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission met remotely in part to address this issue. The request to ban beaver hunting and trapping on federal lands was widely supported during hours-long public testimony by conservation organizations like Cascadia Wildlands, numerous biologists, the Siuslaw National Forest, and many members of the public who wish to see Oregon’s beavers protected. As expected, sportsmen and hunting industry-friendly state representatives opposed the ban.

In an unexpected attempt to block the Commission from voting on the ban, at the end of the lengthy hearing Oregon Department of Justice counsel told the Commission that it could not consider the ban because the notice to the public of the proposed rule change was “inadequate.” The Commission therefore voted at this time not to change regulations, allowing for the continued trapping of beavers.

The fight to protect our beavers is not over, however, as Cascadia Wildlands is planning to file a petition opposing the Commission’s decision. The beaver’s importance to Oregon’s ecosystems and ongoing restoration efforts cannot be overstated, and we will continue to work to increase the number of beavers in our waterways. Thank you to everyone who submitted comments and attended the hearing—we will make sure your voice is heard.

Stay tuned!